Two days ago, Korea celebrated the 80th anniversary of Independence Day. As many of you know, Korea was occupied by Japan from 1909 to 1945. During those years, Japan ruled the peninsula brutally, stripping Korea’s resources for its conquest of China, trying to abolish Korean names and language, torturing and killing those who resisted, systematically forcing Korean women, many of them teenage girls, into sexual slavery for its soldiers, and sending countless Koreans into forced labor across Japan in dangerous conditions, with many deaths. When the United States dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, many Koreans were there as mobilized laborers, working in factories, mines, and other facilities. Nearly 20% of those who perished in Hiroshima were Koreans.

During the Joseon Dynasty, the era of the Enlightenment in Europe, Korea was known as one of the most civilized and technologically and culturally advanced countries in Asia. Yet the Joseon court then suffered nearly a century of incompetent, feckless kings who hindered the industrial and technological revolutions reshaping the world. When American ships came to Japan and Korea to open relations, Japanese leaders opened its doors wide and modernized, while the Korean leaders resisted, eventually forcing the American ships to turn away. With that, Korea stagnated.

Japan, long the “second brother” to Korea in the Far East, modernized its society, industry, and military with breathtaking speed, becoming strong enough to defeat the Russian Empire in 1905, the first time a European power lost a war to an Asian country. Growing ever bolder, Japan’s leaders set their sights on conquering Korea and China—China being the world’s most enduring civilization over millennia—which, like Joseon, had stagnated under ineffectual emperors and lagged far behind other powers in technology and military strength. To link the Japanese military to Manchuria and then to China by land, they conquered Korea in 1909, bringing unimaginable sorrow and tragedy to the Korean people.

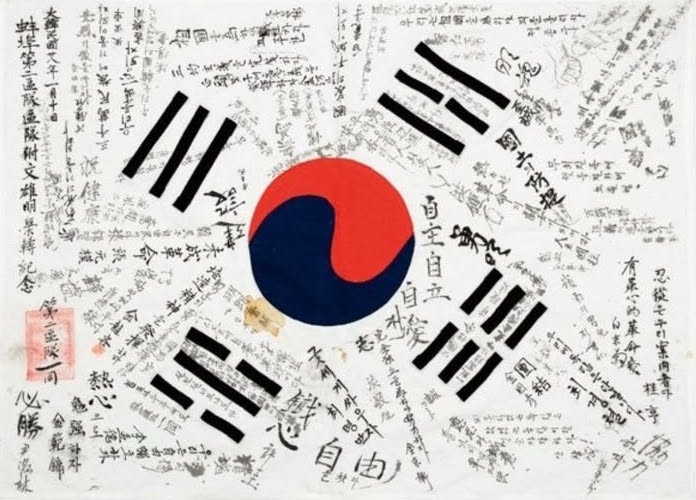

Yet Koreans are a proud people, with 5,000 years of history and dynasties that at times ruled lands stretching from Manchuria to Siberia. Many independence fighters escaped to China and continued the struggle throughout the occupation. When Korea gained its independence after Japan’s surrender to the United States, following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, some discounted Koreans’ role in their own freedom. But Korean independence fighters never stopped fighting, and they would have continued even without American intervention; as China grew stronger, Korea would have fought alongside it and eventually won the country back. Yes, Americans hastened Korean independence, but the last Koreans would have died before giving up. It is this mentality that sustained Korea for 5,000 years, just as that same spirit kept the Vietnamese, Irish, Polish, Nigerian, and Indian civilizations alive, to name only a few.

One curious fact about the Korean independence movement is that its fighters sang the national anthem to the tune of Scotland’s folk song “Auld Lang Syne.” In the late 1890s and early 1900s, before the occupation, many American and Scottish missionaries came to Korea to build churches and schools (the first Korean women’s high school and college were founded by American missionaries). Because of the Scottish influence, “Auld Lang Syne” was already widely used in schools and churches. So when the country needed a sturdy, familiar tune for patriotic verses, what Koreans called aegukga, they set new Korean lyrics to that melody.

Musically, it made sense. The melody is pentatonic, built on five notes, well suited to East Asian ears and easy to sing in unison, which helped it spread quickly through classrooms, churches, and civic gatherings. During the colonial years, independence fighters working secretly in Korea and openly in China—and the Provisional Korean Government in China—used this borrowed tune to carry Korean words, and a shared resolve, wherever Korean people could gather and sing.

By the mid-1930s, composer Ahn Eak-tai judged that a foreign farewell song didn’t suit a national anthem, so he wrote an original setting of the melodies. After liberation, his version was sung at the Republic of Korea’s founding in 1948 and became the official anthem. Still, the aegukga set to “Auld Lang Syne” lives on in memory and in old films and recordings.

Perhaps the most poignant rendition is the one sung by Oh Hee-ok, who, when she died last year at 98, was the last living female Korean independence fighter. She worked as a spy for the Korean independence movement, gathering Japanese police and troop intelligence in Manchuria from age 13 in 1939 until Korea’s independence in 1945. Below is her rendition of the old aegukga to the Scottish tune, sung when then-President Moon Jae-in invited her to the Independence Day celebration in 2017, when she was 91.

Oh, and I hope no one mistakes this post as nationalistic or Japan-hating. I’m a peace advocate and love Japanese culture and people. I’m simply writing about the history of what happened to Koreans in the early to mid-20th century, and about how the old Korean anthem once borrowed a Scottish folk melody.